Josephine Trotter

JOSEPHINE TROTTER : British Landscape

11-23 JUNE 2018

Gallery 8 Duke Street St James’s London SW1Y 6BN

Jenny Blyth Fine Art shows 50 New paintings by Josephine Trotter of British Landscape, Interiors & Still Life

Ann Dumas, curator at The Royal Academy, London writes :

“Trotters latest work shows her at the height of her powers. She is an artist rooted in the tradition of modern Post-Impressionist painting but her deeply felt, poetic response to her native landscape brings a strong and totally individual vision to her subjects. She is a superlative painter in the truest sense of the word.’

…Trotter’s gift for distilling in her paintings that first ecstatic response to a scene brings to mind Van Gogh, an artist she admires. Like Van Gogh, she reacts immediately and powerfully to a motif that she finds compelling…. The sense of rapture that this conveys is at the heart of all Trotter’s work and is expressed, above all, through radiant colour.’

Enquiries: jennyblyth@btconnect.com

Full essay (see below) from JOSEPHINE TROTTER published by Jenny Blyth Fine Art in 2016.

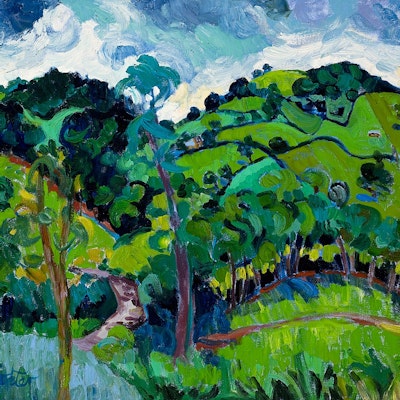

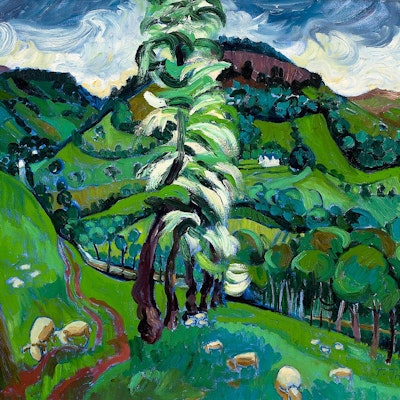

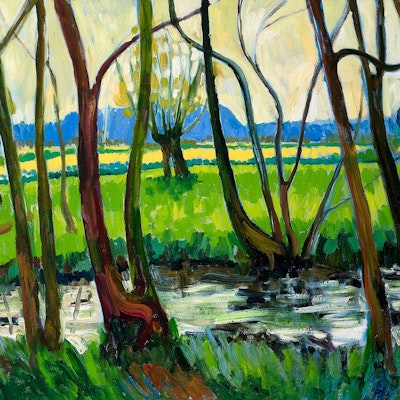

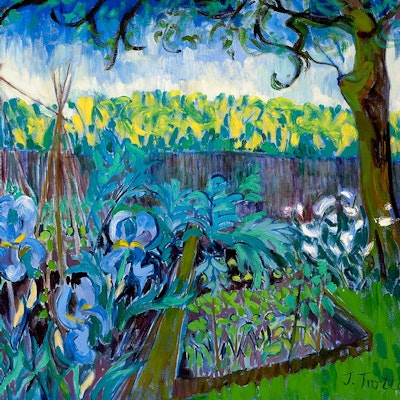

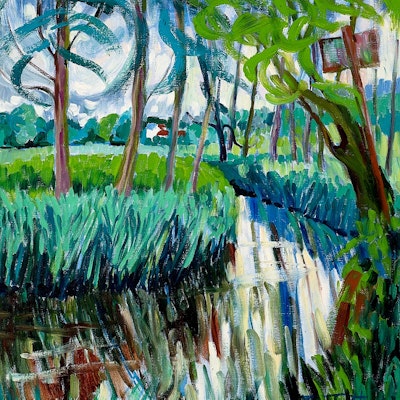

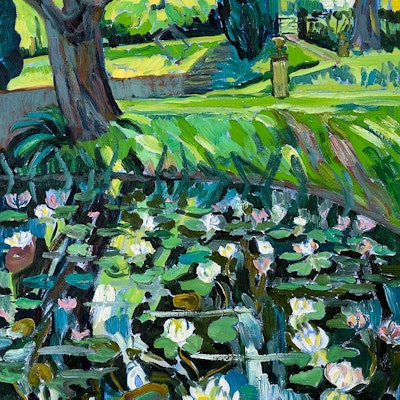

“Josephine Trotter lives at one with the landscape that surrounds her in the Oxfordshire hills. Her home exudes an atmosphere of wellbeing, warmth, nature and art that spills over into the celebration of life that makes her paintings so distinctive. For the last two years, landscape has engaged her most although throughout her long career she has also painted still-lifes and portraits. She has often travelled to paint in sunnier spots, Greece, Turkey, Italy and France, but now it is in the landscapes of Britain that she finds her inspiration, especially in their wonderful variety of greens.

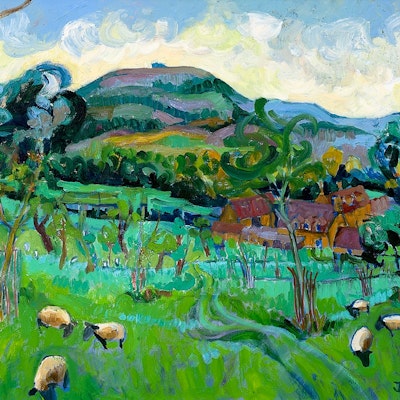

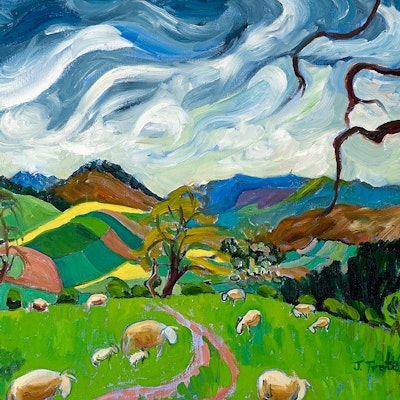

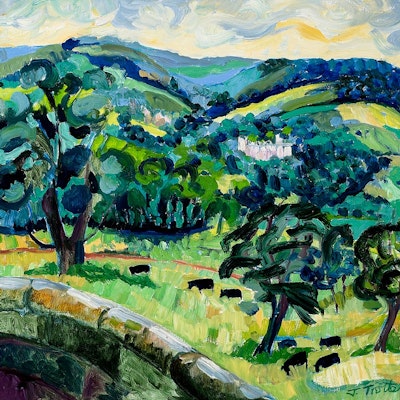

In Brailes Hill in May, 2015 (fig.00) expanses of brilliant yellow rape glow against the fresh spring green fields striped with pink furrows, sparkling in the early summer sunshine. Hills fold into each other, pile up against the sky and culminate in the distinctive profile of Brailles Hill, a local landmark. The sense of rapture that this work conveys is at the heart of all Trotter’s work and is expressed, above all, through radiant colour.

Trotter’s gift for distilling in her paintings that first ecstatic response to a scene brings to mind Van Gogh, an artist she admires. Like Van Gogh, she reacts immediately and powerfully to a motif that she finds compelling. ‘I get an absolute bolt in the head’, she explains, adding ‘I can’t explain it – it’s very powerful.’ Away from home, in Cumbria or Wales, she begins by ‘mapping’ her territory by driving around a region to survey the landscape until she is seized by a particular view. Like Van Gogh, she paints en plein air in a single creative burst, usually finishing a painting in one day. The early morning light determines the feel of a painting. She dislikes the ‘flattening light’ of midday and as the sun moves across her subject throughout the day, rather than adjusting the tones of her composition to the shifting conditions, she remains true to that first light that ignited her imagination. She does no preparatory sketches and never relies on photographs, but draws the broad outlines of the composition with a brush loaded with thinly diluted paint. Once a painting is finished, she never revises in the studio. This truth to nature is often physically challenging. Like Monet struggling with the weather on the beaches of Normandy, or Van Gogh with the Mistral in Provence, Trotter sometimes has to weight her easel with bags of stones to stop high winds carrying her canvas away.

As with Van Gogh, the spontaneity of Trotter’s work belies the thought and the thorough grounding in technique that lie behind it. She may paint quickly but there is no doubt that an innate sense of organisation and structure contribute to the force of her paintings. Her pigments, she explains, are always arranged in the same sequence on her palette and this helps her organise colour relationships on the canvas. And, like Cézanne, she builds up her composition across the canvas as a whole, constantly aware of how each part relates to the whole.

A love of landscape was instilled in Trotter from the very beginning of her career. As a teenager, she took private lessons with the painter Maurice Field, a teacher at the Slade and who encouraged his students to paint in the open air and to record their observation with direct sincerity. He took her sketching in the footsteps of Constable on Hampstead Heath and introduced her to the artist’s oil sketches in the Victoria and Albert Museum. Drawing classes with the distinguished post-war artist Euan Uglow at St. Alban’s School of Art gave her a thorough grounding in draughtsmanship and pictorial structure. At Chelsea School of Art Trotter deepened her understanding of drawing by attending life classes for two hours every evening, a discipline that would have a lasting impact on her technique and her approach. Today, she often sees the swells and hollows of the landscape in terms of the human figure. But, most importantly, at Chelsea she also discovered colour. New paint ranges in tubes offered exhilarating possibilities – ‘at least five different greens’. ‘Colour came bursting out of me’, she recalls, and before long a brilliant rush of colour banished the muted palette of her earlier work.

Not surprisingly, it was in the early twentieth-century colourists, Matisse, Derain and the Fauves that Trotter found her artistic mentors. And it is perhaps in her still-lifes that Trotter is closest to the Fauves. In Red, Yellow and White Tulips with Red Jug, 2014 (cat. 00), the brilliant flowers stand out against and at the same time intertwine with the patterned background. Trotter likes tulips for the way ‘they walk about’ freely on the end of their stems.

She also learned from artists who emphasized the underlying structure of a composition, Georges Braque or Juan Gris, and especially Cézanne whose drawings she studied at the British Museum and who is still the artist whom perhaps she admires the most. Certainly, an innate structure in her own compositions grounds and balances the vivid colour and the emotional immediacy.

Portraits have always engaged Trotter and remain important. Recently, in addition to her family, she has painted with great sympathy a full-bodied professional model, Christine, resplendently naked on a chaise-longue (cat. 00), and Polly, the proprietor of a local bookshop who is celebrated for her colourful attire, in characteristic bright pink stockings and red shoes (cat, The Blue Howgills, Cumbria, 2015, cat. 00).

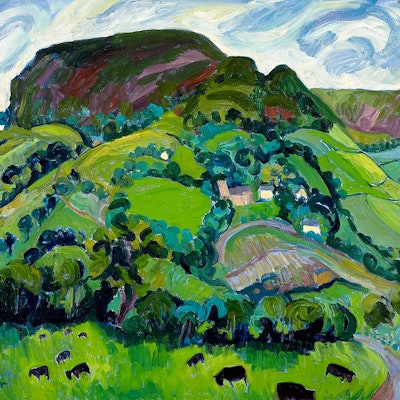

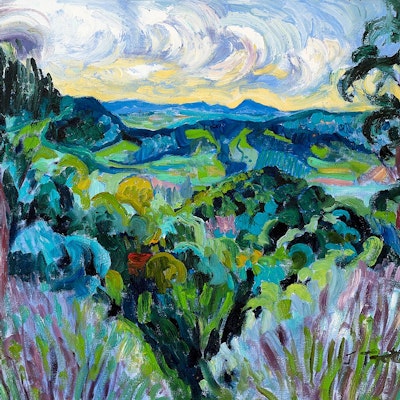

But it is above all in landscape that Trotter has immersed herself in her recent work. She returns again and again to the benign, rolling countryside that surrounds her Oxfordshire home. While this particular landscape is fundamental to her current work, she has also explored more dramatic landscapes in Yorkshire, Wales, Yorkshire and Cumbria. During an expedition to Cumbria in the summer of 2015, she was captivated by the Blue Howgills hills, the rise and fall, the sweep and bend, the fluid shapes of the hills rushing up to the sky – Gerard Manley Hopkins’s line ‘Landscape plotted and pieced — fold, fallow, and plough’ (Pied Beauty, 1877) comes to mind – checked at the top of canvas by the deep blue band of the horizon (cat. 00).

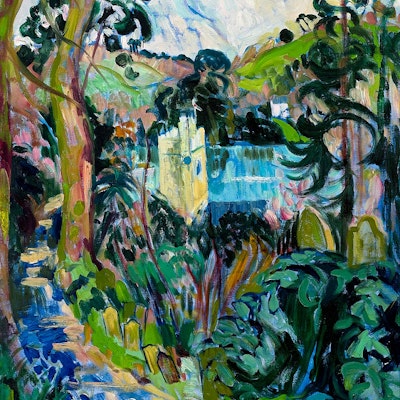

In The Churchyard with Memorial, Betts Newydd (cat. 00) Trotter tackles another subject close to her heart - graveyards. She insists that the subject has no metaphysical or spiritual significance for her but that the appeal is purely visual the strong, geometric forms of the crosses thrusting up through the loose, burgeoning green grass is what attracts her.

Trotter’s latest work shows her at the height of her powers. She is an artist rooted in the tradition of modern Post-Impressionist painting but her deeply felt, poetic response to her native landscape brings a strong and totally individual vision to her subjects. She is a superlative painter in the truest sense of the word. ‘I absolutely love putting paint on’, she declares, ‘I love paint, the smell of paint and its texture.’ In the end, her art is about the stuff of painting, and it is in the visceral essence of the material itself that she has always found herself and the reason why her paintings speak so vividly to us.

JOSEPHINE TROTTER

Gallery 8, Duke Street St. James’, London SW1Y 6BN

13 - 25 JUNE 2016

GREAT BRITAIN

Gallery 8, Duke Street St. James’, London SW1Y 6BN

25 March - 12 April 2014

BRITISH & FRENCH: NEW PAINTINGS

JBFA at The Gallery in Cork Street, Cork Street, London W1S 3NG

6 – 18 June 2011

BRITISH LANDSCAPE & INTERIORS

JBFA at Ebury Galleries London SW1

7 – 26 April 2008

ENGLISH & ITALIAN LANDSCAPE

JBFA at Arndean Gallery, 23 Cork Street London W1S 3NG

15 – 27 May 2006

Martin Gayford, art historian and art critic for Sunday Telegraph and author of ‘The Yellow House and The Man in The Blue Scarf writes

June 2011:

On June 27 1888, Vincent van Gogh wrote to his friend Emile Bernard, mentioning a new picture he had just done of the fields outside Arles. He called it Summer Evening and painted it, he explained, at a single sitting. To rework it was impossible “You see, I went out to do it expressly while the mistral was raging. Aren’t we seeking intensity of thought rather than tranquillity of touch?” Josephine Trotter would no doubt understand exactly what he meant by that. “I’m a very immediate person”, she says, “so I have to have the hype of the subject in front of me”.

A great admirer of Van Gogh, she herself has worked very close to his artistic territory. Last summer she painted below Les Baux de Provence, which is perched on top of Les Alpilles, the blue ridge of which can be seen in the background of so many of his Arles landscapes. In fact, she had a thoroughly Van Goghian experience there. “There was a mistral blowing and you could feel that rage and madness he got into because of this awful hot wind. It does make you feel mad. This painting blew away six times, it was very, very daunting. I had to go back when it had calmed down a bit.”

A shared appreciation of the upside of that maddening wind is by no means the only attitude that Josephine Trotter shares with the great Dutch artist. She too is fond of onions, for example (Vincent was prone to pop them into pictures including Vincent’s Chair (1888), in which a boxful are sprouting in the background). Trotter “There’s something about onions. It’s the shape and the colour: all those different greens and the limes.” Another enthusiasm is irises, which swirl in the foreground of Cuq en Terasses, France (2010). “I’m so madly in love with Irises because I keep thinking about those Van Gogh Irises (1889)”. Above all, like Vincent, she is an artist who has a powerful feeling for the material she uses: oil paint, in all its glorious, glutinous physicality. “I get so excited about paint. During my progress as a painter I have become increasingly fascinated by its quality and application – from Cezanne’s architectural and controlled brush-strokes to the passion of Van Gogh’s.” Oil is her preferred medium; for works on paper she uses gouache rather than watercolour because it has more substance. If a feeling for the substantiality of pigment itself is one affinity that Trotter feels with Van Gogh, another is the emphasis she puts on drawing. Of course, the two are not easily separated, certainly not in Trotter’s case. “I feel privileged to have trained at a time when drawing was the crux and bones of art education and very hard work”.

She was born in 1940, began paint as a child, and was taught life drawing by Maurice Feild before going on to art school. “When I was at Chelsea School of Art, I was taught to draw, draw, draw. We had life-drawing every night for two hours, and the same pose for a week.” Another piece of luck, in her view, was to have been taught by the late Euan Uglow, one of the most gifted British painters and draughtsmen of the post war period.

From this intensive grounding in drawing from life, she emerged with a feeling for landscape that is grounded in human anatomy. “I think there’s a lot of drawing and tension in landscape. I think of my paintings of countryside as rather large nudes, like my model Christine. The contours of the hills give me the same feeling. If you don’t get the fields in right it’s the same as if you don’t get the arm in right. The whole thing falls apart”.

In Trotter’s landscapes, such as Towards Buttermilk, Oxon (2010) you can sense that attitude towards topography – regarding it as an organism, tautly constructed of muscles, bones and sinews. Though this may seem a strange way to think about fields and hills, it is by no means unique. Degas, an artist who spent most of his time painting and drawing human bodies, once produced a picture that is simultaneously a coastal view and a reclining female nude, her limbs formed from the mounds of cliff-side turf.

Degas, however, was – in one of the classifications of artists largely neglected by art historians – an indoor painter. All his work was done in the studio. Trotter on the other hand, in common with Van Gogh and Monet, predominately an outdoors artist. “I can’t finish my landscapes in the studio, when I come back I never touch them ever.”

A battering from wind is only one of the hazards suffered by a painter working out of doors, sur le motif as artists used to put it in 19th century France – though it is one of the worst because a canvas is of course, a small sail, easily blown over or even away (Van Gogh advised tethering one’s easel to the ground with ropes and tent pegs during the mistral).

Especially for a painter like Trotter who is “mad about English landscapes” there is the problem of rain, a great deal of which fell while she was painting Waterloo Bridge. In the South of France, where she painted last year, there is the question of heat. In one case, she had to come back and finish a painting at 6.30 in the morning, “because it was just too hot where I was sitting later in the day”.

In busy places such as the centre of London, where Trotter painted the splendid sequence of paintings of bridges over the Thames, which is the centre-piece of this exhibition, there is the distraction of milling crowds of curious strangers. Van Gogh put up with that too, painting the Night Cafe (1888) on an easel set up in an all-night bar, much to the interest and amusement of the clientele.

Trotter’s London and Tower Bridges from the Millennium Bridge (2010) was done sur le motif on one of the most teeming thoroughfares in the metropolis. In this case her husband claims some credit for its successful completion. “Angus feels he was very important in these pictures, which he was. He was whopping all the tourists away with an umbrella. They were like ants. We were there for seven hours. Angus said to me, “You are so rude!” I explained, “If I talk to anybody, I’d never paint, I have to be so focussed”. If anybody stuck their face in mine I just said I was foreign”.

When painting the semi-castellated Victorian magnificence of Albert Bridge she managed to find a more secluded vantage-point, as she explains: “I’m used to having people breathing down my neck but it’s a relief to escape from them. I was so relieved that I could get into Battersea Park, climb over some iron railings, and sit in some gorse bushes.”

The tricky thing with Lambeth Bridge was gaining access to the pontoon outside Tate Britain, from which it was painted. “I was so frustrated because I got there at quarter past 8 in the morning but they didn’t unlock the chain on the gate until about quarter past 11, waiting for the first ferry, by which time I was having a seizure”.

Trotter’s set of London bridges is not a topographical exercise. It was undertaken out of affection for certain structures – starting with Battersea Bridge, which the painter knew from art school days. It is not, and is not intended to be, complete. Chelsea Bridge for example, was omitted. She went and looked at it, “I didn’t like it at all, it’s very flat and boring.”

There are of course, ample precedents for painting London’s bridges – there’s a Thames-scape tradition that goes back to Canaletto in the 18th century, and includes Turner, Constable, Whistler and Monet. Trotter was especially conscious of André Derain, whose vivacious fauvist London paintings she saw in a remarkable exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery in 2005-6. “I got very emotional about painting Tower Bridge thinking about Derain and those wonderful Thames pictures he did.”

Tower Bridge at Night, her own Thames nocturne, however, is the picture that reached limits of painting sur le motif. A difficulty of painting outside anyway, especially in a country with rapidly fluctuating cloud-cover such as Britain, is the changing light. But what to do when the light goes altogether - that is at night? With the fading of light colour too disappears. For this Trotter explains. “I did some drawings and a little photograph but there were technical problems, I had to rush back and do it inside”. Nonetheless it is one of the most striking of her bridge paintings.

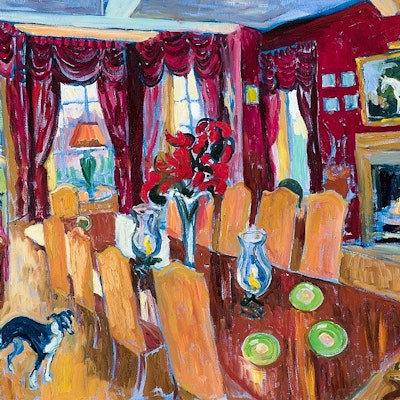

Indeed, Trotter loves painting inside too. Early in 2010 she and her husband were snowed in at their Oxfordshire farm. “It was wonderful, I can’t tell you how wonderful. Nobody could get at you.” As she emphasises, inside or out, “The thing is, I really love painting.” That is abundantly evident from her exuberant work.

William Packer, artist and critic with Financial Times for 20 years

May 2006

Josephine Trotter studied painting at St. Alban’s and then at Chelsea having previously been taught privately by Professor Maurice Feild of the Slade. She has sustained the commitment to painting she picked up so early, not only from him, but variously from such remarkable and demanding artists as Euan Uglow, Ceri Richards and Norman Adams, over what is now a long career. But commitment, as it was indeed for them, must always be something rather more than the simple combination of application and enthusiasm with which it may so easily be confused, no matter how sincerely professed. Enthusiasm is all very well, but, far beyond the immediate exercise, there must be to it too an intensity of focus that amounts to passion, and a persistence in taking the work through to a full realisation, if it is to carry with it any true purpose. Painting passionately is serious business. And Trotter is as serious as she is passionate a painter in just such a sense.

She also remains as transparently enthusiastic as ever she was, and the physical pleasure she takes in the stuff of paint and the act of painting is manifest in everything she does. If anything, it has grown more evident as the years have gone on, her work of more recent years now full of a post-impressionist, fauvist energy, redolent of the artists she has come variously to admire so much – Matisse, Derain and Cezanne, Ivon Hitchens and Paul Nash. The paint is rich on the surface, the palette now clean and bright, the brush-stroke direct and confident, the structure always strong, clear and simple. And the work is full, too, of no less direct a delight in the chosen subject, whether it is the rich domestic landscape of the Cotswolds, the grander sweep of the Yorkshire moors, or hedonistic, sun-lit Italy. Here we have an artist fully in command of her material and technique, as sure of her subject as she is sure of her expressive means, and happy enough to continue as she is, set so easily and confidently in her ways.

Yet clearly she is not so easily seduced. Though so open a pleasure is taken in the work in all its aspects, mere pleasurable self-expression is never its point. It is only the amateur that expects to enjoy himself, and Trotter knows full well, from long experience, that for all its joys, painting is never fun. And she knows too that the passion that informs it, like painting itself, is a contradiction and a mystery to be confronted, tested and disciplined rather than indulged – unfashionable demands that they are, perhaps, in our self-indulgent age. Her paintings may look, therefore, direct and simple in the statement, the product of an hour or two spent in easy, happy circumstances, but they are underpinned by disciplines long studied and hard won – disciplines of close observation, organisation and technical address, of light, space and form. It is a truism of art-commentary that all artists end up painting the same picture, for all the apparent changes of manner and subject over the years – plus ca change …. But it is, after all, in the nature of the truism to contain at least a germ of truth. My own belief, born of frequent experience, is that a true artist’s work does indeed tend to hang together in the end, all of a piece. And to see these recent paintings is not so much to wonder as to anticipate what a Trotter retrospective might tell us of the evolution of her work over her prolific career, and how it comes back in its essentials to itself.

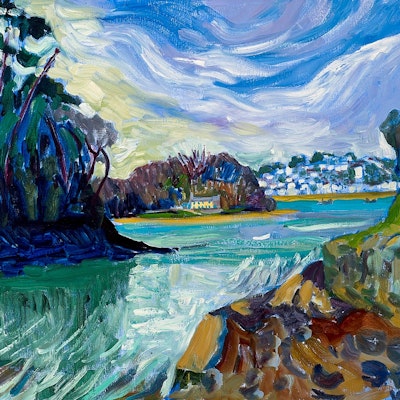

For here still are the landscapes and the interiors that preoccupied her in her student years. The tone may have been pitched so much lower, and the palette so much quieter than today, and there have been intermediate stages along the way, but the sense of an ordered, architectural and inhabited space, though now more often inhabited only by implication, is as strong as ever. The journey from those grey London roofs outside the studio window to the vibrant Manorbier Castle or the church at Cetinale is perhaps not all that far.

Just so, she takes as her subjects just what has come to be familiar to her, whether everyday and close to home in Oxfordshire or what has become so on her travels, for she returns repeatedly to anywhere or anything she finds especially stimulating or intriguing – to the Papal house and its garden at Cetinale near Siena, both inside and out; to the great castles of Wales and England, those vast sculptures in the landscape, Harlech and Manorbier; to the Dorset coast at Bridport and Abbotsbury; to the Yorkshire moors and the Welsh mountains, both north and south. But, as with Chesterton’s ‘Manalive’, we travel far, perhaps, only in order to come home again. And Trotter is no more at home, and no more herself, than when working in her beloved Cotswolds, painting the local fields and farms, and the rise of Brailes Hill that she sees every day.

While she expresses herself so truly and unaffectedly in all this work, the paradox is that self-expression has little to do with it. For self-expression, in art of any kind, self-consciously undertaken, is ever a snare and a delusion – and an irrelevant delusion too, for the simple reason that we express ourselves in any case in everything we do. Rather it is that, as for all artists, for her the difficulty and the eternal fascination lie in the struggle to get it right, of course in terms set by the artist’s own interests and intentions, but only so that the work can then be set free in the world to be taken as it is, standing as it were on its own feet. In even trying to get it right, all true artists do more than they know, and we come to their work not to be creatures of what they think, but to discover what it means to us, and tells us of what and where we are in the world. Josephine Trotter gets it right enough, and we are surprised and engaged by it, and better, for it_. London March 2006. William Packer Art Critic with Financial Times since 1974.” © Ann Dumas 2018